HEVC ( H.265 ) Summary

High-Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) (H.265) is the successor to H.264, which was developed similarly to H.264 by the joint efforts of the ISO/IEC Moving Picture Experts Group (ISO/IEC Moving Picture Experts Group) and the International Telecommunication Union – Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) Video Coding Experts Group (VCEG). The primary goal of the new codec is to provide 50% better compression efficiency than H.264, as well as support for resolutions up to 8192*4320.

The technological background of HEVC encoding

In terms of technological background, the ITU-T began developing a successor to H.264 in 2004, while ISO/IEC began work in 2007. In January 2010, these groups collaborated on a joint call for proposals, which culminated in a Joint Collaborative Team for Video Coding (JCT-VC) meeting in April 2010, at which the name High-Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) was adopted for this codec.

In October 2010, the Joint Collaborative Team on Video Coding produced the first working draft specification, based on eight working draft specifications, and it was approved in July 2012. On 25 January 2013, ITU announced that HEVC had received stage 1 approval of the ITU-T Alternative Approval Process, while the MPEG announced that HEVC had been promoted to Final Draft International Standard (FDIS) in the MPEG Standardization Process.

This essentially means that the initial versions of the specification have been frozen so that multiple vendors can finalize their first HEVC products. The current implementation includes a Main profile that supports 8-bit 4:2:0 video, a Main 10 profile with 10-bit support, and a Main Still Image profile for still digital images that uses the same encoding tools as video “inside” a picture.

HEVC will continue to advance work already underway on 12-bit video extensions and 4:2:2 and 4:4:4 resolution formats, as well as incorporating scalable video coding and 3D video into the specification.

How does HEVC (H.265) encoding work?

Similar to H.264 and MPEG-2, HEVC uses three types of frames—I-, B-, and P-—within a set of images, and combines inter-frame and intra-frame compression elements. HEVC includes several advances, including:

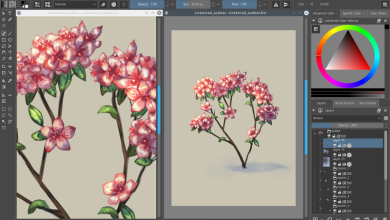

Structure block encoding: While H.264 uses small blocks with a maximum size of 16 * 16, HEVC uses structure block encoding or CTBs with a maximum size of 64 * 64 pixels. Larger block sizes are more efficient when encoding large frames such as 4K resolution. As shown in Figure 1.

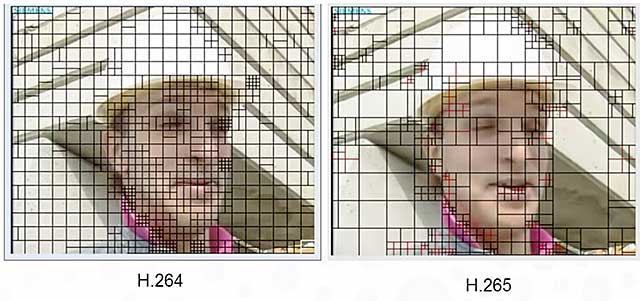

More internal prediction directions : While H.264 uses up to 9 internal prediction directions, HEVC can use more than 35 directions, adding more potential reference pixel blocks and making internal frame compression more efficient (see Figure 2, from an Ateme presentation ). This comes at the cost of additional encoding time required to search the additional directions.

Other developments include:

-

Adaptive motion force prediction, allows the codec to find more redundancy between frames.

-

Superior parallelization tools, including wavefront parallel processing provide more efficient encoding in a multi-core environment.

-

Entropy coding is context-aware binary arithmetic coding (CABAC), not context-aware variable-length coding (CAVLC).

-

Improvements to the block removal filter and creation of a second filter called adaptive sample equalization which then maps the output along the block edges.

HEVC (H.265 ) encoding results

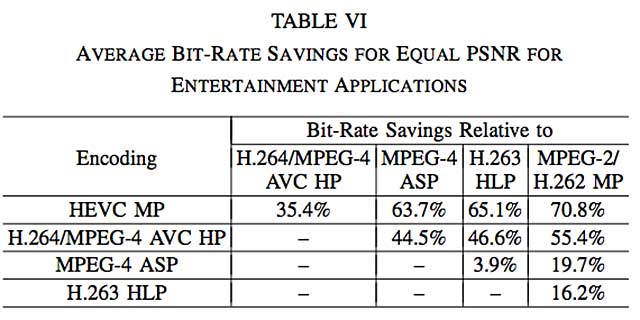

There are a number of reports and presentations that focus on comparing the quality of HEVC versus H.264 and MPEG-2. One of the most widely cited sources is an article titled “ Comparison of Coding Efficiency of Video Coding Standards Including High-Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC),” which shows the results of both PSNR (peak signal-to-noise ratio) comparisons and subjective evaluations. The report looked at multiple scenarios, including interactive and entertainment applications.

For the entertainment comparisons, the study encoded multiple videos ranging in resolution from 832 x 480 (480p) to 1920 x 1080 (1080p). For the peak signal-to-noise ratio tests, the study encoded files using four different technologies—HEVC, H.264, MPEG-4, and H.263—until all files had the same peak signal-to-noise ratio.

The study then showed viewers multiple files encoded at multiple-bit rates using H.264 and HEVC and asked them to rate the results. From these tests, the researchers concluded that “test sequences encoded with HEVC, at an average bit rate of 53% lower than H.264/MPEG-4 AVC HP, achieved approximately the same subjective quality.”

Another article, “ Subjective Quality Assessment of Upcoming HEVC Video Coding Standards,” compared H.264 and HEVC using both peak signal-to-noise ratio and objective comparisons. The study concluded:

The test results clearly show a significant improvement in coding performance compared to AVC. For the natural contents considered in this study, a bitrate reduction of 51 to 74 percent can be achieved based on subjective results, while the expected reduction based on peak SNR values was only 28 to 38 percent. This difference is mostly because peak SNR does not take into account the saturation effect of the human visual system. The peak SNR also does not capture the full nature of the output: AVC compression sequences carry blocks and obstructions, while HEVC compression tends to smooth out the content, which is less annoying. For the synthetic content considered in this study, a bitrate reduction of 75 percent can be achieved based on subjective results, while the expected reduction based on peak SNR values was 68 percent.

It’s reasonable to be at least a little skeptical of these results, since the comparisons were largely produced by experts who contributed to the HEVC effort, using codecs that were either not commercially available or (in most cases) not released for public beta testing. Speaking under anonymity, one CTO at a major encoding company estimated that HEVC could potentially reduce file size by 30% at the same 1080p resolution, with further increases at higher resolutions.

Where will HEVC (H.265 ) work?

Playback statistics are hard to come by. However, multiple companies have demonstrated HEVC playback on a tablet, including Qualcomm on an Android tablet powered by a dual-core Qualcomm Snapdragon S4 processor clocked at 1.5GHz. However, we note that the video was only at 480p, which is fine for a tablet screen but far from the 4K video that HEVC was designed to enable.

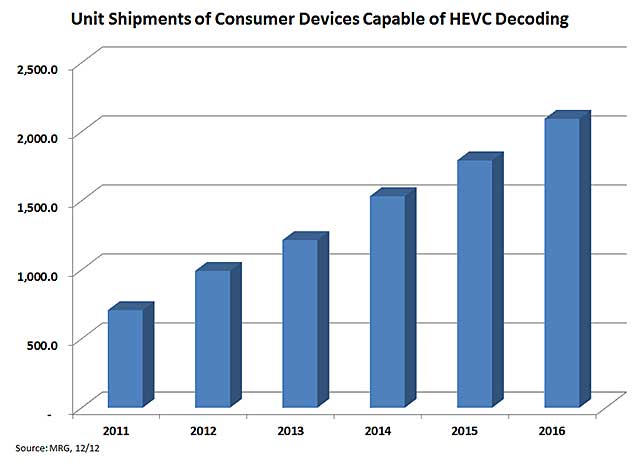

According to a report titled “ HEVC Decoding in Consumer Devices,” senior analyst Michelle Abraham of the Multimedia Research Group concluded that the number of consumer devices sold in 2011 and 2012 that were capable of playing HEVC with enhanced software was approximately 1.4 billion, with more than a billion more expected to be sold in 2013.

According to Abraham, these statistics are compiled to assume that all desktop computers shipped each year will be capable of playing HEVC. The report also includes tables summarizing sales of HEVC-capable tablets, portable media players, streaming devices, video game consoles, Blu-ray players, and digital TVs.

Despite this large established base, Frost & Sullivan believes that HEVC adoption is at least five years away for consumer content services. The delay in HEVC adoption includes forces such as the recent large investments in AVC hardware by a number of pay-TV operators, the lack of widespread support for HEVC in video streaming and encoding across the Internet ecosystem, and the slowness of HEVC encoding and decoding to maintain the profitability of existing AVC chips.

According to Dan Rayburn, vice president at Frost & Sullivan, initial HEVC rollouts will occur in closed-loop solutions such as corporate video conferencing, high-quality video services in the Far East, and low-data-per-second video-on-demand services worldwide, due to the cost savings associated with deploying low-data-per-second HEVC video. Rayburn expects direct-to-home (DTH) satellite providers to begin rolling out HEVC in the 2014-2015 timeframe, with some experimental DTT channels expected in 2015. However, he sums it up in general terms:

While some applications will embrace HEVC much sooner than usual, and HEVC cores should mature by 2014 , we expect a comprehensive ecosystem of first-generation HEVC products to come to market by 2017. Furthermore, we expect AVC to remain in widespread use through 2018, although it will be considered a commodity technology at that point, much like MPEG-2 is today.

HEVC (H.265) Copyright

One factor that may slow the adoption of HEVC is the unknown intellectual property rights surrounding it. Like H.264, many of the technologies contributing to HEVC are patented, and patent holders will want compensation for the use of their intellectual property. In June 2012, MPEG LA, the main association of patent pools and the organizer of the H.264 patent pool, announced a call for HEVC patent filings, and a third meeting of the 25 stakeholders took place in February 2013.

However, according to MPEG LA officials, there is no specific timeframe for issuing royalty guidelines or even ensuring that the patent pool is consolidated, as there are other producers, or because the owners involved may decide to reserve their rights individually. Some market segments, most notably the chip, encoder, and other infrastructure companies, will likely move forward with their HEVC efforts in the face of these unknowns and simply reserve their rights to potential royalties. However, other segments, particularly free streaming content distributors seeking the data savings that HEVC provides, will almost certainly wait until the royalties are finally known.

Competition in view of HEVC (H.265)?

These proprietary rights have made a number of competing technologies such as Google’s VP9 worthy of mention, especially since Google added VP9 decoding to beta versions of Chrome in December 2012, along with a decoder for audio streams encoded with Opus. According to a presentation by Google at the November 2012 Internet Engineering Task Force meeting in Atlanta, the goal of VP9 was to produce quality comparable to HEVC at lower data rates. In a requirements document available on WebM, Google stated that VP9 would not ship unless it improved quality over VP8 by 50% and at a cost of 40% more decoding complexity, compared to 200–300% for HEVC.

As a codec, VP8 compared very favorably to H.264, producing nearly the same quality at all tested data rates. However, a number of factors have ruled VP8 out, including the fact that Apple refused to include VP8 playback in iOS devices or Safari, that Microsoft refused to include it in Internet Explorer 9, that H.264 is a joint standard between the Motion Picture Experts Group and the International Telecommunication Union, and that it came to market much later than H.264.

Many of these factors remain to be seen: While Apple is expected to adopt HEVC, it is unlikely to support VP9 for the same reasons it refused to support VP8, and there are potential intellectual property issues. Additionally, HEVC is a shared standard, so it already has a head start in terms of silicon support for encoding and playback. Furthermore, both VP9 and HEVC are expected to hit the market around the same time, which may give VP9 a better chance than VP8.

Regarding intellectual property issues: In February 2011, MPEG LA launched a call for VP8 patents, and as of July 2011, 12 parties had made progress toward this. However, no further progress is reported on the MPEG LA website, and our MPEG LA contact confirmed that there is nothing new to report.

Moving forward with HEVC (H.265)

Of course, as Frost & Sullivan analyst Rayburn points out, HEVC can’t be deployed until the encoding, decoding, and transport processes are fully in place. Some encoder vendors, such as Elemental Technologies, have announced that all existing encoders will be retrofitted to support HEVC via software upgrades at some point in the future. Before you buy a business or desktop PC from now on, ask whether it will support HEVC and how much that support will cost.

Moreover, the prospects for HEVC are market-driven. For example, in video conferencing, the opportunity exists for real-time HEVC encoders and decoders. In the media streaming space, playback is always the driving force, as few producers will encode to a new format until it is clear that it can work reliably for a meaningful audience.

For general broadcast purposes, it’s hard to get excited about HEVC without:

-

MPEG LA Intellectual Property Policy

-

Play everywhere via HEVC encoding in a player like Flash Player or Silverlight Player (Neither Microsoft nor Adobe responded to requests for information on when and if this would happen).

-

Integrating HEVC playback into iOS or Android, either via an app or an OS update, and clearly announcing which hardware will support HEVC with these upgrades (given both companies’ longstanding policy of not commenting on future technologies, we didn’t even ask them about that).

-

The availability of inexpensive silicone jaws that can be incorporated into streaming devices, or the announcement that some existing streaming devices will be able to be retrofitted to play HEVC via software or OS upgrades.

Conclusion

Between NAB (April 2013) and IBC (September 2013), we expect a wave of HEVC-related technology and product announcements. During that time, the first wave of HEVC-capable devices will also hit the market, providing an opportunity to measure the performance, costs, benefits, and interoperability of HEVC video streaming in the real world.

Until then, as Frost & Sullivan notes, it’s best to look at HEVC adoption in microcosms rather than macrocosms, as the economic drivers and prospects are different in each market. While the general purpose buzz around HEVC is tied to its popularity, what matters is how those announcements impact the markets they serve.